Black, Hispanic/Latino, and Asian Americans have been historically underrepresented in the veterinary profession. In fact, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, these minority populations make up less than 13 percent of the 83,000 veterinarians in the US.

Aspiring vets, especially minorities, want to be able to see themselves in the profession through the faces of those who are already working in it. A lack of diversity in the profession also impacts the animals and pets being cared for. Many people from low-income areas may not have access to or can’t afford pet healthcare.

Acting on the need to make the profession a more inclusive and diverse field, the American Veterinary Medical Association and the Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges announced plans last year to create a new commission addressing diversity, equity, and inclusion in the veterinary profession.

To that end, three recent graduates of St. George’s University’s School of Veterinary Medicine shared their perspectives on the issue of diversity in the field and how they plan to make a difference by paying it forward.

Breaking Barriers as a Latina

Atalie Delgado, DVM ’20, an intern at Med Vet Chicago, fell in love with animals on her family’s ranch in Mexico and with becoming a veterinarian. However, she struggled to find support from Latina women who were pursuing degrees as veterinarians—a notion she aims to help fix. Dr. Delgado recently secured a residency position in small animal emergency and critical care at The Animal Medical Center in New York City that she will begin in July.

SGU: What inspired you to enter veterinary medicine?

Dr. Delgado: My strong desire to pursue a degree in veterinary medicine was built on a foundation of love for animals and a deep understanding of the intricate relationships that humans have with animals. The lack of Latinas in the sciences has motivated me and reaffirmed my desire to establish myself as a leader within the veterinary community and to mentor students of Latino origin who are just starting their veterinary medicine education.

SGU: What do you see as the biggest issue in vet medicine?

Dr. Delgado: The lack of open dialogue and support that minority students often face. The promotion of diversity starts with educating future veterinarians and creating safe spaces where students of color feel supported.

At SGU, I gained the confidence to advocate for minority students and women in veterinary medicine. I started the SGU Women’s Veterinary Leadership Development Initiative (WVLDI) student chapter during my second year of vet school with the help of my classmates, faculty, and staff at SGU. I am eternally grateful to have spent three years with supportive colleagues and faculty who encouraged our endeavors to promote diversity and leadership on the island and in the veterinary community.

SGU: What do you love about your job?

Dr. Delgado: Working at a busy specialty center in an urban area of Chicago allows me to practice my medical Spanish while also providing quality care to pets of clients who come from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds. It’s through these experiences that I continue to grow as a clinician and strengthen the aspirations I have as a veterinarian.

Obtaining board certification in emergency and critical care residency will help me to advance my career in veterinary medicine and support my desire to teach and advocate for diversity in the field.

VOICE: Championing Diversity in the Veterinary Profession at the Student Level.

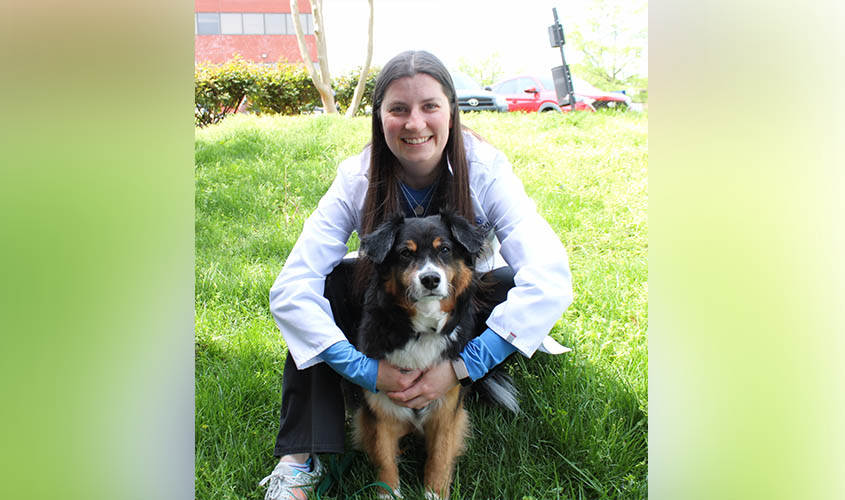

Empowering African Americans to Become Veterinarians

Amber Shamburger, DVM ’19, is a small animal general practitioner in Gardner, MA. Originally from New York City, she became interested in veterinary medicine at a young age, becoming laser-focused on pursuing her dream once she entered high school.

Dr. Shamburger began volunteering at a veterinary hospital during her summer vacations, where she gained a mentor. “My mentor played a remarkable role in getting me to where I am today,” she said. “Not only did she teach me so much, but she also opened so many doors for me with the opportunities she offered.” Through her experiences, she hopes to inspire more African American and Hispanic vet students to follow their dreams.

SGU: What do you see as the biggest issue in vet medicine?

Dr. Shamburger: I never realized how much diversity was lacking in this profession until I started vet school. The lack of diversity was quite painful, in stark contrast to the very diverse education I was exposed to years prior. It is important that we strive for diversity in vet med because it will help our profession grow. It will help us relate to our patients more, offer different treatment protocols among different populations, and offer unique perspectives.

SGU: What does it mean to you to be an African American and Hispanic woman in the field?

Dr. Shamburger: To be an African American woman in this field is empowering. Being Hispanic breaks down even more barriers. Although veterinary medicine is dominated by women, it is true that I represent a statistical anomaly. I hope, however, that I may also represent an example to other African American women that may have never considered this profession, to pursue their passion with ease of knowing that it is attainable.

SGU: What do you love about your job?

Dr. Shamburger: I love that I have the ability to reassure an owner who is concerned about their pet, whether it’s through education or by offering a plan of action. I also love that there is never a dull day in this profession. I can always count on seeing an interesting case and having the opportunity to learn and grow from it.

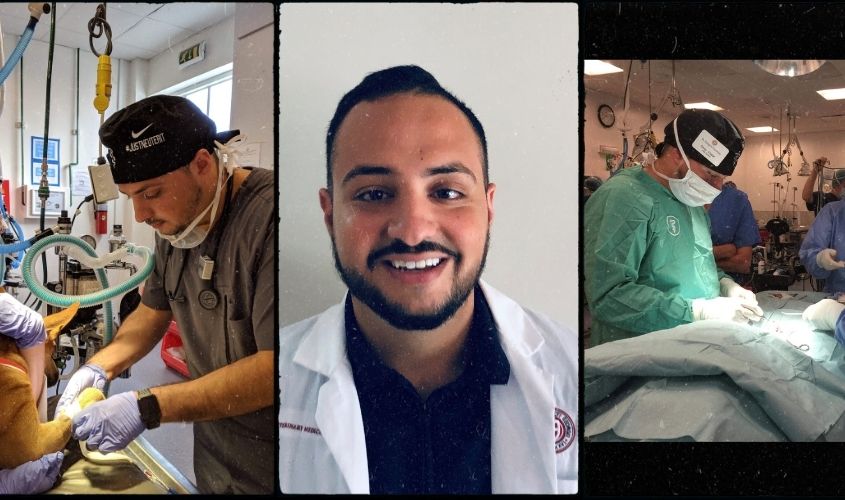

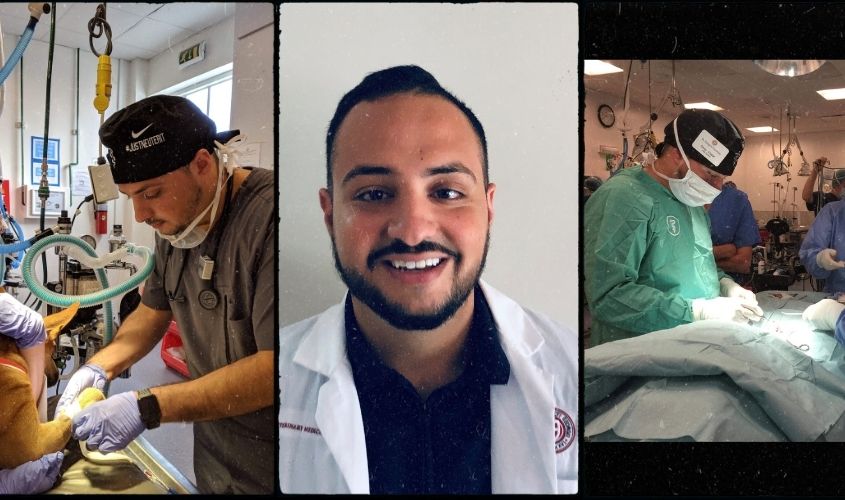

Raising Awareness of Pet Care Outside the US

Growing up, Dr. Omar Khalaf found himself drawn to animals and their well-being, and that feeling only intensified when he would visit his family in Jordan. The lack of vet care available in the country, and education about the profession in general, motivated him to study veterinary medicine at SGU. Following his January graduation, Dr. Khalaf secured an emergency medicine/small animal rotating internship in Hollywood, FL.

SGU: How were you inspired to enter the field?

Dr. Khalaf: My defining moment was being in Jordan as a kid and seeing many uncared-for stray animals and the lack of education of how to care for them.

SGU: What do you see as the biggest issue in vet medicine?

Dr. Khalaf: The lack of education of the importance of veterinary medicine—and as a result a lack of priority placed on creating veterinarians—in non-American countries to ensure the health of animals there. However, this is beginning to change and as a result we are seeing vets from all different ethnicities and cultures.

I hope to be able to raise awareness of the importance of animal and pet care through education and through social media to people across the world.

SGU: What do you love about your job?

Dr. Khalaf: Being able to help sick and critically ill animals return to good health and live happy lives. The reward and smile of seeing people seeing their animals healthy is priceless.

— Laurie Chartorynsky

As the coronavirus pandemic brought the world to a halt, Eric Vail, MD ’13, went from cancer geneticist to COVID-19 diagnostician and researcher.

As the coronavirus pandemic brought the world to a halt, Eric Vail, MD ’13, went from cancer geneticist to COVID-19 diagnostician and researcher.